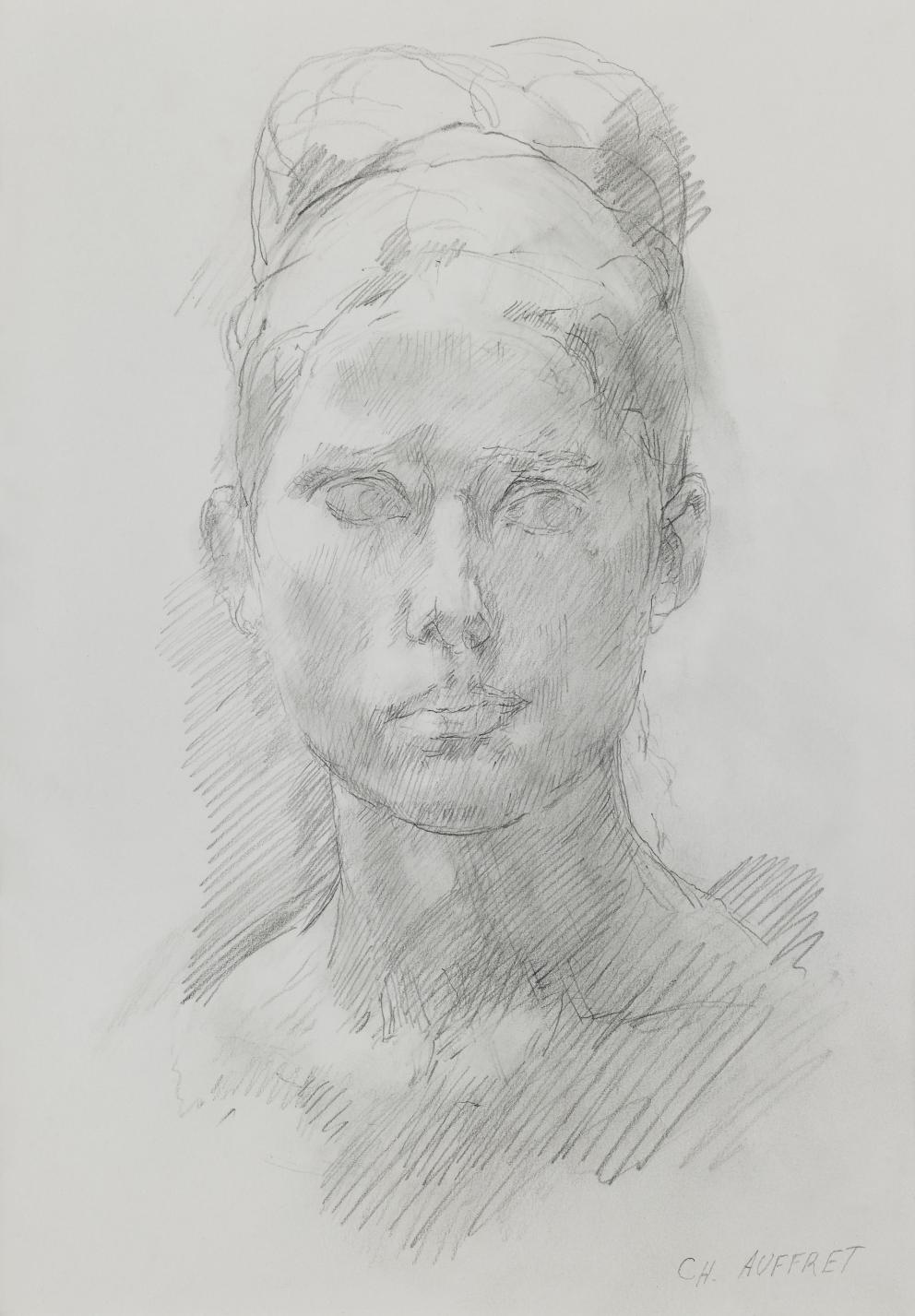

Five Questions for Arlette Ginioux

This interview with Arlette Ginioux was done by Marie Flambard in June 2023 during a visit to the sculptor’s studio (Paris’ 19th arrondissement).

1

Arlette Ginioux, you’re a sculptor, and you work in Paris, and you developed alongside Charles Auffret, sharing both your family and artistic lives. What would you like to say about his personality, the kind of man he was—and how did you both reconcile everyday life with your creative life?

He was an intelligent and pragmatic man, with exceptional qualities. We shared a life of work. We’d go on vacations always only to work. We’d get up at 6 in the morning in order to capture the right light, at Bandol or elsewhere. The only thing that really mattered to him was to be in his studio.

For a while, we shared the same models and the same studio, but not for long … We each had to work in our own way. We didn’t talk about our creative work that much. In 1965, he got a grant from the Fondation Ricard to spend a year in residence on the Île de Bendor in the Var. That summer was a beautifully creative period. I did some lovely things—a medal of Auffret, the bust of the legionnaire Gonish. We were relieved of material considerations.

2

When two people share art and life as you two did, the influences must be numerous and rich—can you say what traces he left in your creative development?

He taught me so much; he taught me to see. He was an excellent teacher. We’d go to the Louvre to look at Rembrandt together. We admired Camille Claudel, August Rodin, Charles Malfray, Jane Poupelet, Germaine Richier, Alberto Giacometti … He introduced me to creativity. He’d talk about the unity of things, of how to find an architecture. When you have a common vision, an abstract vision, you have everything … I admired his work. His advice was always important to me; he had an extraordinary eye. He’d comment on my drawings. We’d give each other suggestions. And he’d also listen to what I said, my advice. He trusted me.

3

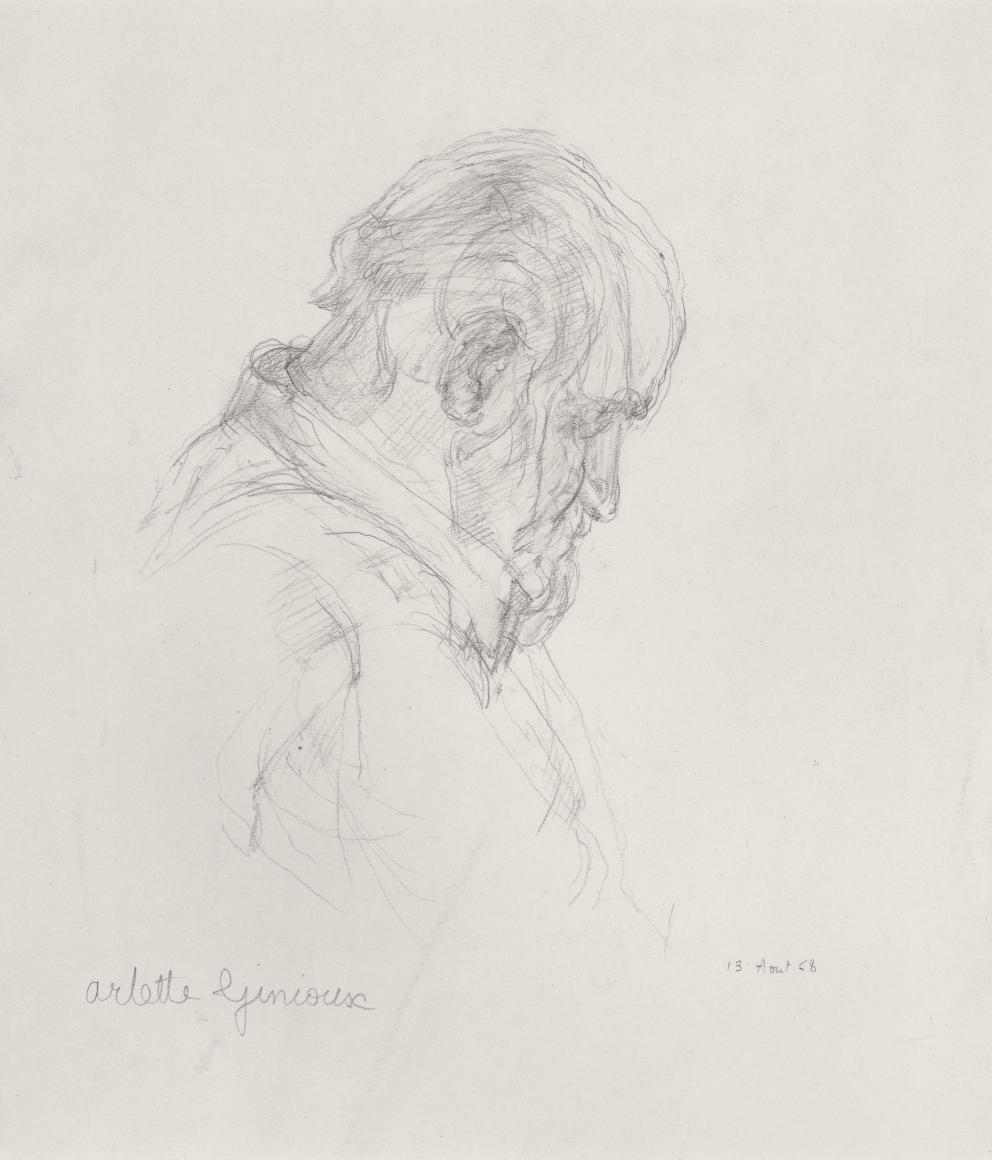

You often appear in Auffret’s art; you were his muse—there are portraits of you, both sculpted and drawn. Is any one of those depictions particularly dear to you? And if so, which one?

He did beautiful portraits. I posed for him and received much in return. I could observe and learn so much by watching him work. There are portraits drawn, engraved, and sculpted, but there are no busts. Of his work, I’m particularly fond of a portrait that he did of me in lead pencil. It’s a really beautiful drawing—taut, lively, as luminous as a marble.

4

Charles Auffret was a professor at the ENSAD (École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs) for ten years, and he left a vivid memory with his students. One after the other affirms that he was an extraordinary professor, a great teacher. As you also taught for years at the ENSAD, what can you tell us about it.

I was his student at the Malebranche Academy; Richard Peduzzi was also there. He was a really great professor; he himself had been at a great school and had learned from Pierre Honoré [Pierre Honoré, 1908-1996, sculptor], at Dijon. We worked intensely. Every morning, we had a model. His language spoke to me; I understood it—he taught seeing—it was so strong.

At Arts Déco, he gave the Wednesday afternoon drawing course, and everybody went. He was greatly admired.

And then, in turn, I taught drawing and sculpture at the ENSAD. At the time, drawing was the spine of all the disciplines, though that has completely changed.

5

In an important interview from 1997 (THE NEED FOR DRAWING), Charles Auffret explained his vision of drawing. What do you think of that text?

When one is at the apprentice stage, it’s important to gain the fruit of the experience of a good professor. Charles Auffret’s statements in that text are timeless; they apply to every era. In it, he broaches the true problem. You can sense the legacy of Rodin, for example, when he discusses working from the Antique. For me, the reference points in terms of drawing are Cézanne, Bonnard, Rembrandt, Titien … A sketch by Bonnard or Rembrandt touches the head, the heart, and the gut. It’s authentic, true, it comes from the depths! We were both convinced that you have to go through a serious apprenticeship in order to assimilate the inherent laws of drawing. The artist can then express who he or she is.